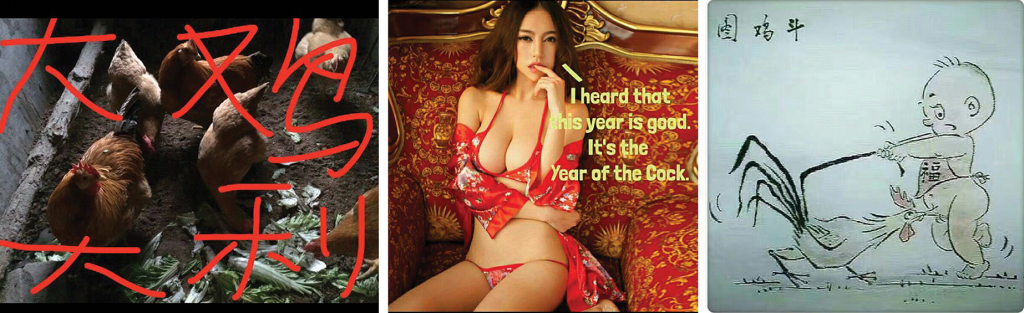

大鸡大利 | Year of the cock

It’s a joke so obvious and trite that I tried very hard to avoid it, but eventually everyone around me was cracking it, and sometimes the cheapest jokes become fascinating because of their own over-emphatic and meta-humorous repetition. So Happy Chinese New Year: 2017 is the Year of the Cock, which most English-language speakers politely translate as Year of the Rooster. The bilingual pun is interesting in itself, since cock and 鸡 ji function as parallel phallic euphemisms in both languages (attested since 1610 in English, of muddled dialectal provenance in Chinese), and the slightly altered blessing 大鸡大利 da ji da li (‘big cock, big profit’) emerges effortlessly as the local version of ‘Happy Year of the Cock’. I spent my first Spring Festival in China in 2010, throwing firecrackers and dodging firework shells in the backalleys of Huangpi Nan Lu, right in the middle of the most intense new year celebration I’ve ever experienced (and I’ve lived through New Year’s Eve in Italy for twenty-plus years, just to claim some pyromaniac street-cred). After a few years of absence, I have then been repeatedly back to Shanghai for Chinese New Year during my fieldwork in 2014, 2015, and 2016, witnessing the progressive urban silencing of the celebration. This year I left China one week earlier, and I decided it was time to jot down some thoughts from fieldnotes I kept taking about the traditional holiday and its circulation on social media.

I remember how, even during my MA degree, the trademark obsession of an engaged sinologist was to religiously watch the entirety of the chunwan gala in search of hidden transcripts and policy subtexts, and then discussing them at pub tables for the following week or so, spicing things up with expert criticism of xiangsheng comedy sketches. Chunwan hermeneutics haven’t changed much, and each Lunar New Year’s Eve year academics and China-watchers alike join the celebration by rediscovering the guilty pleasure of a one-night stand of cultural critique, hanging their latest sociopolitical arguments on the catchy hooks of popular spectacle and national television. I guess I’m an outlier – over the past few years’ Spring Festival evenings, I have watched the chunwan for a few minutes at most, adopting pretty much the same degree of spectatorial commitment of the people I was spending the holiday with: occasionally turning my head to the TV while fetching snacks or drinking a beer or sending greeting messages or failing to catch a hongbao on WeChat. For the most part, I learned about the highlights of the televised galas through the remediations of Weibo posts, shaky WeChat videos of funny or trashy moments captured on huge LCD screens in crowded living rooms, and the trail of humorous images circulating on social media during the remaining weeks of the holiday.

Of course, the chunwan gala is an integral part of the modern experience of Spring Festival in Mainland China, along with horrifying trips back to one’s hometown in the midst of the largest annual migration in the world, handing out or receiving hongbao (from actual paper envelopes to WeChat messages and Zhifubao location-based treasures), sending copy-pasted greetings to one’s entire contact list, setting off fireworks (increasingly severe bans notwithstanding), and eating a lot of hearty family food while coyly complaining about the whole experience. But I’ll focus on the TV program here. Chun Peng, in Chunwan, art and authoritarianism, gives a perfect summary of the entertainment behemoth:

Chunwan, or Spring Festival Gala, is a household name in mainland China. For those unfamiliar with the term, it is a special variety show produced by the Chinese Central Television Station (CCTV) that has aired on the eve of every lunar new year since 1983. The latest version was broadcast live on the evening of February 7, with an audience claimed to be 1.033 billion, a dazzling figure easily dwarfing any comparison. For what it is worth, the most watched broadcast in American TV history, the 2015 Super Bowl finale, drew a record viewership of 114.4 million. So it is not at all an exaggeration to say that Chunwan is the most watched show in television history.

Yet, while the chunwan has anchored the convivial experience of Chinese New Year across hundred of millions of living rooms for almost twenty-five years, its paratext of digital media interactions and vernacular content has recently opened up a transversal dimension of engagement jutting out of relatives-packed private homes, towards the social circles and networked publics articulated by the personal use of digital media platforms.

Even last year, when WeChat was undeniably the preferred route for group hongbao exchanges and personal season’s greetings, Weibo remained the hotbed of critical commentary on the televised Spring Festival gala. “This is very good – would be even better if they didn’t talk”, someone commented on a photo of an ethnic minority dance number. A popular humor account uploaded a photo of an elderly woman with a stern expression, circled among the televised audience, with the caption: “I don’t really understand the humor of young people”; a friend of mine reposted it commenting: “Actually, young people don’t understand chunwan humor as well”, and another common friend added: “I’ve been dumbstruck for the entire evening”. Besides the widespread criticism of chunwan humor falling flat on most spectators, criticism of the event itself was also a topic of discussion. A widely followed verified account posted a screenshot of a chunwan broadcast covered by scrolling comments in Japanese: “It came out! It’s the first time that the Japanese website Niconico streams the chunwan online, come and take a look at the full transcripts of the refreshing ways in which Japanese audiences tucao it with scrolling comments” The question of tucao, ‘mocking’, was a central point of contention last year – as Yan Feng, a well-known local academic commented:

This needs an explanation: in the era of the Internet, tucao is a kind of love, it is the embodiment of interactivity on new media, it becomes in itself a structuring and constitutive part of aesthetic activity. Tucao transforms dissatisfaction into happiness, taking tu (vomiting) for le (pleasure) […], it transforms negative elements into positive elements, it helps getting unhealthy feelings off of one’s chest, it is in fact a very good practice of harmony and stability. If there is tucao, this proves that there is a positive participation. If one day there were no tucao, that would be truly dangerous.

Along with the Weibo comments on the performances, humor, and the meta-criticism of tucao itself, each chunwan leaves in its wake a paratextual trail of iconic images and widely debated content. In 2016, this trail included lamentations on the crackdown on VPNs usually coinciding with national celebrations, the circulation of a reportedly censored essay titled “This chunwan is a spectacle of the Zhao family” (the “Zhao family” being a recently rediscovered euphemism for bureaucrats), as well as the punctum-like still frame of a parade of humanoid robots dancing in Guangzhou. One of the earliest comments on the technological showcase I read on Weibo playfully approved it: “Chunwan, from now one put more robots in the program, ok?”, and yet a year later the image has accrued a resonating iconicity as a symbolic signifier for techno-orientalist imaginations of the country. As Yuk Hui writes:

In February 2016, during the famous annual TV programme of the state-owned CCTV for celebrating the Chinese New Year, the climax came at the moment when five-hundred and forty robots danced onto the stage, with the singer trilling ‘rush, rush, rush, dashing to the peak of the world…’ while a dozen drones leapt above the stage and shuttled back and forth between the laser lights. This is perhaps the scene that best symbolises the likely future of the Anthropocene in China: robots, drones—symbols of automation, killing, immanent surveillance, and nationalism. One wonders how far the popular imagination has already become detached from the form of life and moral cosmologies that were central to the Chinese tradition. (2016: 298)

What were this year’s Spring Festival traditions? I haven’t paid much attention to the celebration this time. There were, as usual, photos of larger and larger TV screens broadcasting the gala floating around WeChat. Some friends sent hongbao in our chat groups – it was a record year, as usual. Others complained about VPN services, suffering an even more institutionalized crackdown around the holidays. Someone reported that WeChat was deleting messages encouraging audiences to avoid watching the chunwan. More and more people expressed their disappointment at the increasingly rigid bans on fireworks. Right before and after the Spring Festival gala, some videos hosted on Bilibili made the rounds on social media: one was grainy black&white archival footage from “China’s first chunwan, the 1956 Spring Festival Gala“; the other, a humorous piece by the Shanghai Hongqiao Choir titled “Spring Festival Self-Help Guide“. The thousands of danmu comments scrolling on these two videos encapsulate the spectrum of remediated paratexts extending the chunwan experience back in history and forward into meta-commentary, across living rooms, memories, social networks and connected devices.

Again, Happy Year of the Cock.

References:

– Hui, Y. (2016). The question concerning technology in China: An essay in cosmotechnics. Falmouth, United Kingdom: Urbanomic.

– Peng, C. (2016, February 19). Chunwan, art and authoritarianism. The Diplomat.