废俗 | Junklore

“Redundant information, calculated as, say, the number of stickers in corners, on walls, on lampposts that it takes to build cognizance of this information in one subject, may immediately be understood as informational by another subject.” (Fuller 2005, p. 36)

As a general rule, I try to post on this website only original pieces put together from scraps of unused notes or jotted down as drafts for eternally forthcoming articles. The following text is a semi-exception, since it’s something I wrote more than a year ago on commission for a book sprint held at Shanghai’s One Space in October 2014 in conjunction with the Junkware workshop, and which resulted in the publication of The Junk Venture Book. The whole Junkware project was an art experience wonderfully orchestrated by Qu Hongyuan, Julien Maudet, Catherine Lenoble, Sophia Lin, Clément Renaud and Merryl Messaoudi in occasion of the 2014 Shanghai Maker Carnival, and revolved around an exhilarating combination of DNA sequencing, generative design, 3D printing and Taobao binge-shopping. The starting point of the workshop was Thierry Bardini’s 2011 book Junkware, and the goal of the book sprint was updating or forking its theses under the conditions of contemporary computational landscapes. I condensed my responses to Bardini’s book under six points, augmented here with some photos for mildly speculative ambience.

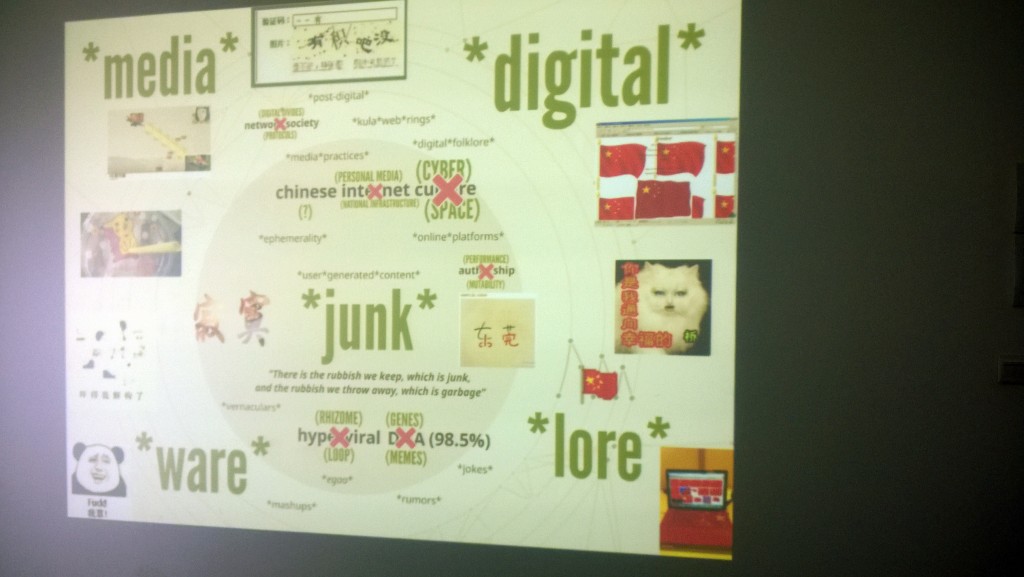

*digital*media*junk*ware*lore*

*数*媒*废*品*俗*

Shanghai mediations on Thierry Bardini’s Junkware

*junk*

废物 (feiwu, garbage)

“There is the rubbish we keep, which is junk, and the rubbish we throw away, which is garbage”, Sydney Brenner reportedly explains on page 49, inspiring Thierry Bardini’s call for a semantics of discard. Of the many questions elicited by the signature of *junk* – what is junk? Everything / when is junk? Now, and more to come / where is junk? Everywhere / who is junk? Us, and them / how is junk? Good and bad and useful and useless, it depends, yet it’s 98.5% of everything – perhaps the most sensible question to ask today remains so what?, or, why does it matter?, or, why does junk matter? and why does matter junk?

*ware*

无用的 (wuyong de, useless)

A materialist approach to junk and a junkist approach to matter seem the most useful moves to derive from Bardini’s portmanteau *junk*ware*: stuff that is the Other of stuff, in time and place and ownership and use, things that are temporarily thrown in a limbo of less-thingness and uncertainty, accumulating in heaps of problematic matter, losing the boundaries which segment them in individual objects, rewinding back the process of individuation by piling up upon other junk. The next step leads into speculative junkonomics: a recuperated copy of Marx’s writings encoded in the wrong character set postulates the W-J-W and J-W-J cycles, from ware to junk to ware, and from junk to ware to junk, the accumulation of capital sustained by use value superseded by the self-sustaining accretion of use-less value circulating across stacks of 品 pin, ‘ware’.

*digital*

垃圾邮件 (laji youjian, junk mail)

The fabled Internet of Things is in fact merely the polished 1.5% portrayed by the aseptic photos of data centers and the colorful network diagrams appearing on sleek PowerPoint presentations at international industry talks. What about the non-signifying 98.5%, then? Where is The Internet of Junk? Who collects and sorts out *digital*junk*ware*? What other forms does junk take in our digital and already postdigital times, besides the obvious junk mail already made almost invisible by the perfected algorithms of our filters and the pop-ups preemptively killed off by our AdBlock plug-ins? How does this digital junk get repurposed into digital ware and when does digital ware goes back to being digital junk? Is even junk a fitting metaphor for the platitude that user-generated content is?

*media*

信息毒品 (xinxi dupin, information drug)

Bardini’s writing is irremediably double-helixed, knitted along the polymer bases of its own DNA, as it proceeds by a sort of augmented dialectics set in motion by hidden third terms – media. DNA is made of genes, but genes are 98.5% junk, and junk matters; culture is made of memes, and memes are just like genes, so 98.5% of culture is junk, and it matters too. The jump from these parallels into the hidden third of hypervirality is legitimized through the figure of the loop, which becomes the organizing aesthetic trope of our times after the deleuzian fold. In hyperviral culture, the augmented dialectic loop continues, memes are the genes of culture, and memes work like mind viruses, so that “a virus is essentially junk code, and our hyperviral culture is indeed a junk culture” (p. 189). The viral metaphor mediating between memetics and genetics pierces through half a century, from Burroughs and cybernetics to Derrida, Deleuze and Dawkins, and turns *digital*media*junk*ware* into an updated version of selfish cultural DNA – an information drug poisoning minds with alluring rumors and spreadable beliefs. But the non-signifying discard bites back: if meaningless genes cannot be selfish, how could meaningless memes be?

*lore*

无用之用 (wuyong zhi yong, the use of the useless)

“How did this happen? How and when, exactly, did our culture turn to junk? Or, in other words, when did we actually last create some radically new cultural experiences? And when did we instead start to recycle culture with the appearance (the glitter) or the new?” (p. 169) – how many useless questions, Thierry! Let’s tear them apart and build a new toolbox of unusable concepts. If our entire culture turned to junk, it might be the right time to go back to folklore. Junk refuses to be yet another final statement in a series of grand narratives. Junk has to be found in opposition to use value and organic garbage. Junk has to be rummaged into for its discursive making, its affective collection, and its temporary autonomous phases of repurposing into non-junk. Let’s do away with both the myth of the original and the myth of the copycat: 山寨 shanzhai has gone all the way from junk into a culture into a product into an industry into a rhetoric into a narrative and its hermeneutics – junk for academics, the last rodents in line. Let’s stop searching for our next brand of culture when the last choice is as paradoxical as junk. Let’s drop our sampling devices and drift along the kula rings of useless discard that we traverse and traverse us at every corner of our mediated lives. Let’s accept the loss of authorship and preservation, of traceability and evolution, let’s just get high on information drug, let’s believe and preach and sing and dance in a carnival of *digital*media*junk*ware*lore*, a repertoire of noise not-yet-useful to anyone, rumors without referent, fractal jokes, non-human grotesques, post-linguistic vernaculars, unsuccessful memes, self-censoring 恶搞 egao. Makers: let’s “make do” rather than “make to”.

*?*?*?*?*?*

Sketched above are some mediations on a constellation of semantemes recuperated from the reeky dustbin of recent media theory, in the attempt of hacking together new hybrid concepts for a materialist anthropology of the contemporary under the sign of *digital*media*junk*ware*lore* or *数*媒*废*品*俗*. In this light, moving from Bardini’s bio-cultural parallels into speculative probing of the *digital*, *junk* is understood as the Other of *ware*, locked in J-W-J and W-J-W cycles of which we are the *media*, the silent hyphens articulating a *lore* through each change of phase. The best use to which we can put the signal-to-noise ratio of our genome is unmasking the cultures to which we subscribe as ordered and stylized collections of memes, a mere 1.5% of the webs of meaning we code without end. Praise the 98.5%.

References:

– Bardini, T. (2011). Junkware. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

– Junkware. (2014). The junk venture book. Shanghai, China: Junkware.

– Fuller, M. (2005). Media ecologies: Materialist energies in art and technoculture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

09. April 2016 by Gabriele

Categories: Uncategorized |

Tags: digital folklore, hardware, innovation, junk, materialism, media ecologies, Shanghai, software, Thierry Bardini |

Leave a comment