Chinese queries | 百度一下

屌丝一个: “Seriously speaking, is 100 wan enough to get out of China?”

飞飞: “You Baidu yixia first, see which country is a bit more reliable”

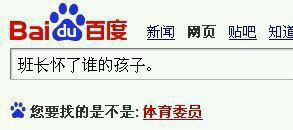

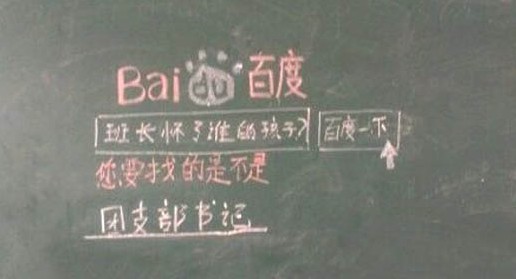

Failed suggestion for the search query 班长到底怀了谁的孩子 – Did you mean ‘sport commissary’?

This post is a companion piece to a discussion going on during the last weeks over the Chinese Internet Research Network mailing list (subscriptions welcome), stimulated by fellow OII researcher Han-teng Liao’s idea of exploiting the Baidu autocomplete function as a tool to “gauge the curiosity of users”. The questions discussed were the following: given that our Internet use is largely channeled by search engines, and given that most of search boxes feature some form of autocomplete or query suggestions, what can we social scientists make out of this sort of digital object? Can suggested queries be exploited ‘as they are’ to collect sets of data about search preferences and quantitative trends? Can they be tapped for samples to be used in cross-national comparative analyses? How should we approach these media artifacts?

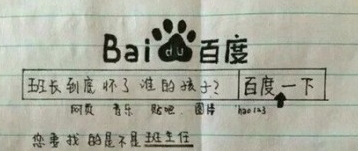

Hand drawing of the incongruous Baidu query suggestion 班长到底怀了谁的孩子, shared online, collected on 打酱油 dǎ jiàngyóu

My first answer to these questions is a general warning regarding the necessity to demystify the transparency of the autocomplete function and of query suggestions, reminding ourselves that search engines are ultimately corporate black boxes driven by algorithmic adjustments and daily fine-tuning that we researchers have very little insight into. Scholars in critical media studies have been exposing the workings of our Society of the Query for quite a while, and Min Jiang has recently published a paper on the specific case of China, comparing the concentration of search results on Google, Baidu and Jike. Paradoxically, the accumulation of partial insights without access to a transparent and complete overview of how a specific search engines aggregate and prioritize results complicates the work of researchers: we discover that suggestions don’t simply depend on a mean average of global searches, but are influenced by language, geography, search history, results rankings, chronological freshness, content filtering, legal cases, controversies, corporate choices, advertisement and so on. And even with the tools we can code, or thanks to the helping hand of digital methods, what we can do at most is often just obtaining some degree of automation and consistency for what would otherwise be a drudging and complicated routine of data collection, while what happens behind the search box remains a matter of speculation.

Collettivo Carmine, “Query Oraculum” (2013) – “when will”, 12-frame animated .GIF image (495x282px)

Despite these uncertainties, search engines’ query boxes have often been not-so-strange attractors for academic research and artistic practice. The work of Pascal Jürgens in reassessing the real impact of filter bubbles, for example, shows that digital methods can be deployed in the social sciences with a certain degree of validity and help answering specific research questions. Collettivo Carmine’s 2013 artwork Query Oraculum, to which I contributed, condenses a year-long sampling of the suggestions triggered by four English-language existential questions into looping .GIF images, visualizing the temporal changes of the ranking and the influence of news events and technological recurrences (“when will windows 8 be released?”; “when will facebook timeline be mandatory?”). Similarly, the delightful GooglePoetics gives quadruplets of autocompleted results a literary edge by framing them as postdigital haiku of everyday knowledge.

GooglePoetics autocomplete haiku, June 1st 2014

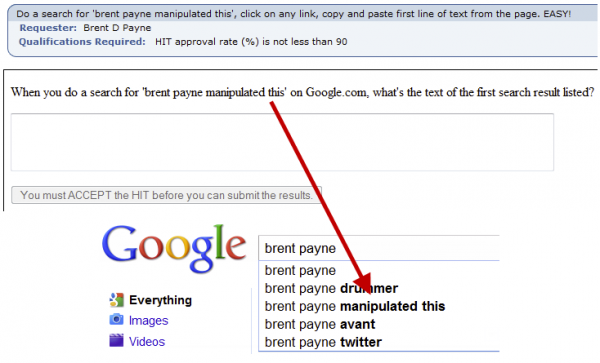

Yet, as Hanteng notes, this line of work is a purely descriptive or at most interpretive one, and still relies on arbitrary choices of sampling. His proposal is instead to build onto the concept of black box as theorized by cybernetics and control theory, and to find ways to hijack search engines by rerouting their inputs and outputs: “even if the search engine companies prevent us from knowing the inner working of the black box, we can still *steer* the outcomes by creatively and systematically feeding the new inputs based on what we know from the outputs.” What Hanteng is proposing here is in line with hijacking practices like Google bombing favored by digital media activists and Search Engine Optimization professionals alike.

Brent Payne demonstrating Google autocomplete manipulation through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk

It’s a fascinating technical domain, yet it clearly falls in the category of action research and would require extensive work on the ethics of manipulating search engine results. In fact, Google and most other search engines are constantly engaged in fighting query bombings, SEO strategies, spam and exploits, potentially rendering years of interventionist research useless with one simple algorithmic fix. A sad example of this is Steve Kemple’s 2011 piece “i don’t know” OR “i dont know”, which used “a simple Boolean query to bring form to collective uncertainty then allowing it to disperse once more into the cloud”: after Google fixed the exploit upon which the piece was built, the artwork’s URL now results in a page vaguely (and ironically) stating “Your client has issued a malformed or illegal request. That’s all we know.”

Original output of Steve Kemple’s “i don’t know” OR “i dont know” (2011)

My second answer is a more constructive and qualitative one: to be able to say anything about search engines and their functions, one should inquire about how people use them. Without a deep insight into the shifting levels of trust that users put on search engines, into the biases that the feel they have to compensate for, into the social semantics of querying, and into the actual efficacy of query suggestions to influence usage or sway users, cracking the black box of autocomplete by tinkering with its inputs and outputs may have little sociological relevance. This is especially crucial in the context of nationalizing Internet governance and local digital cultures that shape the approach to search engines while also feeding back into their results. Simply assuming that “users may feel frustrated or even powerless when they encounter machines/systems such as search engines” seems to fall into the enlightened false consciousness mode of social scientists seeing power everywhere.

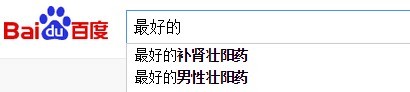

Screenshot of 最好的 (‘the best’) query on Baidu, shared on QQ as a funny image, collected on 打酱油 dǎ jiàngyóu

During my fieldwork, I’ve experienced the sudden blockage of Google Search in China on June 4th 2014, and listened to different people detailing their relationship with search engines on often humorous terms – complaining about Google’s censorship, ridiculing Baidu’s limitations, or discussing VPNs. The proliferation of humor about search engines shows how these digital artifacts are in fact already included in everyday life as elements of our postdigital cultures: users might not be waiting for critical media scholars to figure out the epistemological implications of suggested queries, and to express them in humor and popular wisdom. In fact, Baidu will have a lot of work to do to dispel its negative image of ‘search engine with Chinese characteristics’ and to rebuild a form of trust: as one of my interviewees put it, “the education, the Chinese education, it never tells you to search for the truth, to find the truth, to confront sources, to not only use Baidu for your searches…”

Baidu’s Diaoyu Islands doodle, September 2012

As a specific example of how qualitative insight might help direction research on search engines, I will highlight some very superficial impressions gathered from Hanteng’s initial scraping. The first batch of Baidu autocomplete results he posted on his blog were elicited by a query pairing the word “why” (为什么) with a geographical descriptor. The result, as expected, seems to be a repertoire of national stereotypes and intercultural curiosities: 为什么日本人叫中国人支那人 (‘Why do Japanese people call Chinese people zhina ren?’), 为什么美国人喜欢把钱卷起来 (‘Why do Americans like to roll up banknotes?’), 为什么香港人讨厌大陆人 (‘Why do Hong Kong People dislike Mainland People?’) or 为什么大陆不能上facebook (‘Why can’t the Mainland use Facebook?’). Yet, these questions are for the most part quite specific and link towards issues that could be explored in more qualitative ways: Internet governance (the blockage of Facebook), the politics of translation (the Japanese term zhina ren), media representation (wads of dollars in American movies), and local tensions (unwelcoming Hongkongers).

Blackboard sketch of the incongruous Baidu query suggestion 班长到底怀了谁的孩子, shared online, collected on 打酱油 dǎ jiàngyóu

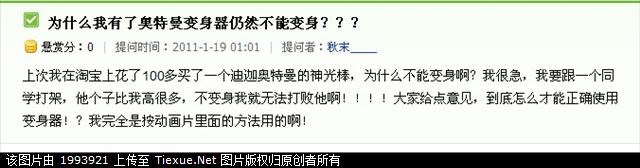

An even more striking example of how digital cultures natively hijack results rankings is highlighted by the first suggested result of the general “Why” query, as reported by Hanteng in his second post: 为什么我有了奥特曼变身器 (unfortunately translated through Google Translate as ‘Why do I have turned control Altman’) is actually a catchphrase that has become popular after someone posted on Baidu the question ‘Why do I have Ultraman’s transformation item yet I still can’t transform?’, originating scores of funny responses. As a user on the Tiexue forum recounts:

“haha, I am laughing to death, today I was searching stuff on Baidu, and as soon as I input ‘Why’ it immediately results in this ‘Why do I have Ultraman’s transformation item yet I still can’t transform?’… when I read it through I laughed my ass off”

“哈哈,笑死我了 ,今天在百度上搜东西,输入为什么,就出来了这个“为什么我有了奥特曼变身器仍然不能变身” 看完我笑喷了”

Screenshot of the original Baidu question “Why do I have Ultraman’s transformation item yet I still can’t transform?”, posted on the Tiexue BBS

Users have noticed, and laughed off, and traced back, and joked about, the incongruity of the first suggested Baidu result for the common query “Why”, just as they have done about 班长到底怀了谁的孩子 (‘in the end, the class representative is bearing whose child?’), the first result which at some point Baidu suggested for the term 班长 (‘class representative’). Are these series of jokes a sort of search engine folklore? Urban legends of the query? Autocomplete humor? As GooglePoetics notes, “Google writes poetry on subjects that people are truly interested in”: without a careful and culturally informed qualitative work, the very human background of this kind of machine-poetry written by search engines is bound to be inevitably lost in automated scrapes and translations.

Original screenshot of the incongruous Baidu query suggestion 班长到底怀了谁的孩子 (‘in the end, the class representative is bearing whose child?’)

Anyway, my intention is not to turn the whole debate into a sterile iteration of the usual qualitative/quantitative scuffles, but rather to turn the edge of critical media theory against itself and propose ways of understanding search engines through their users before throwing ourselves in interventionist enterprises. Search engines collect and organize mind-boggling amounts of information, to the point of being able to track epidemics and organize relief actions after natural disasters. But they are also machines to extract profit from data, and their workings remain (necessarily?) obscure, definitely more algorithmically slippery than any feedbackable cybernetic black box. Turning a search engine into a self-cannibalizing mechanism seems hardly possible – Google Will Eat Itself in more than 200.000.000 years, according to recent forecasts – but surveying them from different perspectives and depths can only result in richer and more contextual understandings of our Societies of the Query.