打酱油 | Digital folklore & Tumblr as a research tool

What the notebook adds to this strategy of alliance with the fetishism of commodities, however, is that the very instrument of research is a fetish. In English we have a phrase, “set a thief to catch a thief,” the idea being that a thief knows best the mind of another thief.

– Michael Taussig, Fieldwork Notebooks, 2011: 6

Eight months ago, right in the middle of my field(net)work in Mainland China, I created an archival Tumblr for my current PhD project and I started experimenting with the integration of image blogging into ethnographic research. The simple three-column, pink-background image gallery was designed as the second iteration of a similar blog I put together years before around the idea of collecting digital folklore from the Chinese Internet. That first version was simply called Chinternet, and remained online for a few months: Tumblr eventually suspended the account on charges of disseminating ‘child pornography’. I had came across a humorous picture of a naked Chinese toddler playing with a kitchen knife on Sina Weibo, and following the rather naïve assumption that whatever could be posted on a Chinese social media platform (usually the benchmark of censorship and suppression) would also be ok on Tumblr (a platform which incidentally hosts quite a lot of porn and gore content), I posted it on Chinternet without much hesitation. After a few days, in an ironic first-hand experience of cultural norms and platform governance, I found my entire Tumblr account under non-negotiable lockdown without any forewarning or take-down notice, and I was back to square one. Luckily I had all the content archived on my hard drive.

The first image I posted on the Chinternet Tumblr (now dǎ jiàngyóu), an animated .GIF of a piece of ASCII art on glittering starry background collected from an early Chinese web page.

The new incarnation of this Tumblr, which I started off by simply reposting the content of Chinternet in the original order (minus questionable pictures of minors), and which I keep updating on an almost daily basis with new items from the chronological archive of images collected during my fieldwork, is called 打酱油 dǎ jiàng yóu. In Chinese, the compound dǎ jiàngyóu literally means ‘getting soy sauce’, but in the local online slang it has been adopted as a figurative way of saying ‘minding one’s business’. I like the term for two reasons: first, it is a good example of a vernacular expression emerging from the feedback loops between mass media (the original TV news broadcast in which a recalcitrant interviewee used the locution to express his extraneity to the event), digital media (the online platforms where the episode was commented and popularized), and everyday communication (in which the compound is extremely popular). Second, as a sardonic expression of disinterest or detachment from a larger situation or social event, I find dǎ jiàngyóu to be the perfect bit of ‘local knowledge’ to explain the main argument of my doctoral dissertation: that the digital folklore circulating on Chinese digital media platforms is a great source of insights into how Internet users in China are just ‘minding their own businesses’.

“I already can’t leave the Internet / Because going online is so cool / I already can’t leave the Internet / Because going online from my company is so fast / Going online is really wild / Going online makes people happy” (anonymous graffiti poem)

Initially set up as a database to help me visualize and search through the objects appearing in my everyday digital media feeds, reveal thematic patterns, or stimulate uncanny correspondences – a sort of small-scale cultural analytics à la Manovich, or a more qualitative version of Weiboscope – dǎ jiàngyóu has become an important resource in other ways. On the one hand, each time I shared the blog with someone participating in my research, the open nature of the platform facilitated the participation of visitors, who would occasionally contribute content from their own digital media feeds, widening the scope of my data collection. On the other, as a dynamic and flexible archive of the digital objects I’m studying, the Tumblr page has become the friendliest way to kick off an interview, elicit discussions in a focus group, and present my research project in a visually interesting way to both colleagues and participants.

The full-body wool suit, currently the most shared and liked item on the dǎ jiàngyóu Tumblr, with more than 5,000 notes

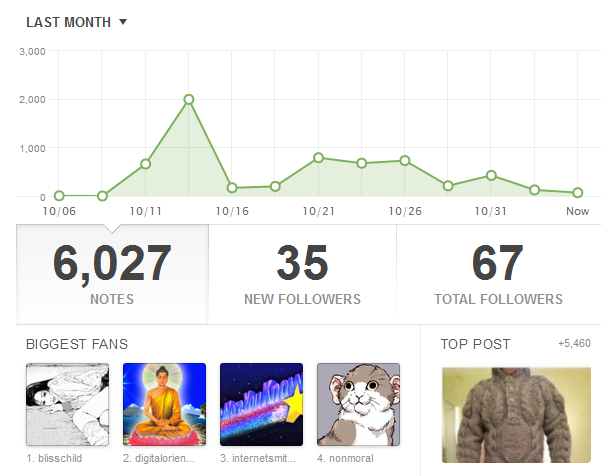

The specific features of Tumblr as a digital media platform also contribute to the dissemination and reception of one’s work. Besides being easy to set up, open to anonymous contributions and, most importantly, still accessible in Mainland China, Tumblr also hosts a very peculiar userbase: the dynamics resulting from the quick cascading chains of liking and reposting individual entries across aesthetic communities can sometimes grant an unexpected, very large exposure to an individual post and, as a consequence, to the entire blog. As a case in point, the image above, a screen-cap of a NewSMTH BBS user showing off a full-body suit knit by his mom, successively widely shared on Sina Weibo, got more than 5,000 likes or reshares in the couple of days after I posted it on dǎ jiàngyóu, resulting in twenty-some new followers.

Tumblr analytics of one month of activity on dǎ jiàngyóu, including the peaks of content popularity and the biggest fans

As a community of users passionately engaged in consuming, contributing, curating and circulating visual content, maintaining a research output on Tumblr can also function as a test-bed for theoretical constructs and aesthetic intuitions. Through chains of serendipitous reblogs, thematic tagging and casual browsing, users tend to follow each other according to aesthetic preferences, and form overlapping communities of interest crowdsourcing different configurations of similar bodies of content, stimulating cross-pollinations, and making one feel less alone in his archival routines. Among the people who intersected dǎ jiàngyóu in these few months of activity, I happened to find some who are also approaching Chinese digital folklore from different and complementary points of view: Michelle Proksell’s netizenet, an online gallery of Chinese net art, and her visual explorations of Digital Orientalism; the vernacular styles of Accidental Chinese Hipsters, and their cooler counterparts on The Beijing Hipster; the jarring juxtapositions of textiles on Fuck Yeah Chinese Fashion, and the series of homoerotic content collected by Fuck Yeah Chinese BL. To each their own fetish!

Comments (2)