Selfies | 自拍

In “Dim Stockings”, a short chapter included in his The Coming Community, Giorgio Agamben takes a cue from the prosaics of a stockings advertisement to discuss the commodification of images and bodies. His recognition of the industrial scale at which the production of body-images happens in contemporary visual regimes doesn’t really come to us as shocking given the concentric simulacra of mediated lives we are by now so accustomed navigating: a peek through most Instagram or Facebook feeds illustrates quite clearly how, as production and circulation become increasingly inexpensive and proportionately nudged by the unquenchable appetites of content farms, representations seem to lose their theological punctum: “Neither generic nor individual, neither an image of the divinity nor an animal form, the body now became something truly whatever” (p. 48).

Statues of a couple taking a selfie, Ximen area, Taipei

Continuing his musings regarding the reflective surface of the whatever-body-image, Agamben ends up formulating a convoluted but rather striking reflection on the decline of portraiture: “the perfectly fungible beauty of the technologized body no longer has anything to do with the appearance of a unicum that troubled the old Trojan princes when they saw Helen at the Skaian gates” – there’s no more mystery in the imaged body, in short – but this loss “is also the basis of the exodus of the human figure from the artwork of our times and the decline of portraiture: The task of the portrait is grasping a unicity, but to grasp a whateverness one needs a photographic lens” (p. 49). Is Agamben possibly outlining here a materialist theory of the whatever-in-selfies?

A wide selection of selfie sticks, smartphone clamps and clip-on camera lenses sold at a street market in Taipei

The intellectual fascination for selfies isn’t easy to explain away solely with the morbid attraction drawing academics and op-ed writers towards whatever practices happen to conjoin extreme visibility and triviality – in itself a long history going from stocking advertisement to vernacular photography on digital media. Selfies have also become a peculiar site of ideological contention and spectacular clickbait: do selfies empower or disenfranchise? Are selfies “a woman thing“? How paradoxically dangerous can selfies be? At a more speculative level, self-presentation and self-representations mediated by contemporary computational media are being imaginatively connected to issues well beyond the usual suspects of cultural distinction and media panics: citizenship, surveillance, consensus, protest, and so forth.

A MOMAX Selfie Pro touchless selfie stick for sale in Hong Kong

For the past year, I have been researching and writing about selfies in tangential ways, for the most part focusing on the selfies taken and shared by social media users in Mainland China. Given the ubiquity of mobile devices in the country and the popularity of social media platforms among local users, my choice might seem obvious, perhaps exotically naive, and at the same time perplexing: does this focus imply that Chinese users take selfies differently? Is the average Chinese selfie whiter, cuter and skinnier than the American one? While large-scale analyses are probably best suited to provide a comprehensive answer to these kind of questions, it is worth mentioning that in the People’s Republic vernacular photographic practices have followed a peculiar path, from the intimate privacy of quanjiafu (family portraits) in Mao’s China, often aesthetically defined “against the centrality of photographic propaganda” (Huang 2010, p. 673), through the popularization of amateur photography during the 1980s, up until to the advent of digital media and cameraphones over the past decade.

Besides the debatable aesthetic differences between local make-up preferences, a Google Image search query for “Snapchat selfies” and a Baidu Image search query for “WeChat zipai” show how selfies are similarly constructed as gendered image-bodies across national platform contexts

Zipai, literally ‘shooting oneself’ (as in shooting photos or videos) is how selfies are called in Mandarin Chinese. The term zipai functions as both a verb and a noun, plural and singular, and can be expanded into locutions such as zipaizheng (‘selfie disorder’), zipaiji (‘selfie tool’, a common name for any imaging device with a front-camera or a reversible screen), or zipai shenqi (‘mystical selfie artifact’, a quirky name for selfie sticks and other facilitating devices). Zipai doesn’t share the cute overtone typical of the the English language suffix –ie, common in neologisms like hippie, fixie, foodie, selfie or tinnie. The character zi simply means ‘self’, while the character pai, as suggested by the ‘hand’ radical on its left side, indicates a variety of actions like ‘paddling’, ‘beating’, and ‘sending’. Taking selfies in China is a quite pragmatic action described by a general term applicable to any imaging device – after all, one could take self-portraits even when the most popular device was a cheap automatic film camera.

The boundary between digital cameras and smartphones blurs as zipaiji and zipai shenqi struggle for a market share by experimenting with reversible screens and swiveling lenses

At the same time, it would be impossible to understand the popularity and whateverness of zipai in contemporary China without a materialist account of consumer optics and social software. It is widely documented how, throughout the past decade, the introduction of low-resolution cameras on mobile phones represented for large sectors of the Chinese population the first contact with vernacular photography (Wallis 2013). More recently, the craze around increasingly cheap and powerful shanzhai smartphones has brought the pleasures of megapixel-quality imaging to large masses of users ready to snap, store, zoom in and leaf through hundreds of photos of their daily lives. Pioneered by the Japanese multinational Kyocera in 1999 and originally implemented for the purpose of video-calls (Okada 2005), the appearance of front cameras on mobile devices has merely transformed a previously blind-guessed exercise into a work of precision and self-fashioning. And in China, the tech factory of the world, front optical sensors haven’t been the last step: reversible screens, rotating cameras, selfie sticks are all technological extensions aimed at a market of affordances defined by zipai – the practice of taking a picture of oneself.

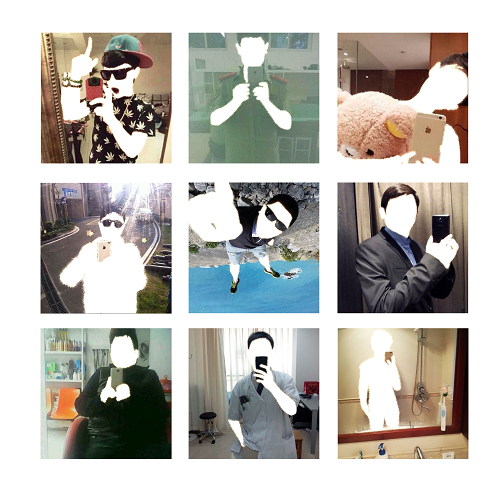

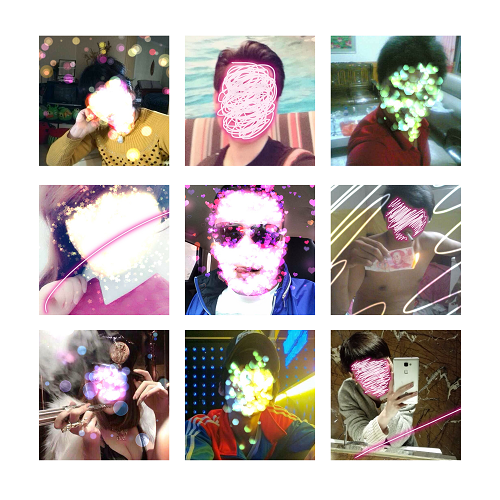

Michelle Proksell & Gabriele de Seta – “Zipai #9 (With Phones)”. Composition of found WeChat images edited with Meitu Xiuxiu. 5737 x 5737 TIFF image, 172MB

Technology isn’t all that there is to zipai. An apparently individual and self-centered activity can easily become the testing ground for new forms of mediated sociality: taking selfies with friends fills the boredom of waiting or moving through urban spaces; snapping group self-portraits becomes a moment of experimentation with the theatrics of cuteness; collective zipai transform the mobile device into a portable photo booth specialized in self-portraiture. Just as Instagram and Snapchat support the whirling dissemination of millions of selfies in Euro-American networks, apps like WeChat, Meitu Xiuxiu, Weipai, Faceu and a slew of other social contact platforms and image editing software provide the channels, the formats and the filters shaping the circulation of zipai across Chinese media ecologies.

Michelle Proksell & Gabriele de Seta – “Zipai #4 (Magic Brushes)”. Composition of found WeChat images edited with Meitu Xiuxiu. 5760 x 5760 TIFF image, 140MB

It is this circulation of vernacular photography that inspired an ongoing research collaboration with Beijing-based artist & curator Michelle Proksell. Some provisional results of our WeChat-based crossovers between performance art and media anthropology have been recently published on Networking Knowledge and, in a less verbose way, displayed at a gallery in Sydney. I have also had the pleasure to interview Michelle about her ongoing work as a collector of vernacular photography for her own exhibition on NewHive, and her app-based curatorial activities have been getting a well-deserved exposure, especially after the riveting talk she has given at this year’s Chaos Communication Congress in Hamburg. I’m glad I helped her register a Sina Weibo account back in 2012.

“Zipai #4” and “Zipai #9” exhibited in the Portable Domains exhibition at Firstdraft gallery, Woolloomooloo

Perhaps, rather than keep engaging in comparative clickbait or nostalgic mourning of a long-lost punctum, questions around selfies and other practices of self-representation should move away from moral panics and superficial comparisons towards questioning how bodies, technologies and images are deployed, along which affordances and against which agencies, in these forms of vernacular photography. The return of self-portraiture through vernacular photography could start to be seen as performing an important task: grasping the whateverness of socialized technologies, and embracing the prosaic and reflective surface of the body-lens-image-screen itself.

References:

– Agamben, G. (1993). The coming community. (M. Hardt, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

– Huang, N. (2010). Locating family portraits: Everyday images from 1970s China. Positions: Asia Critique, 18(3), 671–693. http://doi.org/10.1215/10679847-2010-018

– Okada, T. (2005). Youth culture and the shaping of Japanese mobile media: Personalization and the keitai Internet as multimedia. In M. Ito, D. Okabe, & M. Matsuda (Eds.), Personal, portable, pedestrian: Mobile phones in Japanese life (pp. 41–60). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

– Wallis, C. (2013). Technomobility in China: Young migrant women and mobile phones. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Pingback: Press – michelle proksell