打酱油 | Digital folklore & Tumblr as a research tool

What the notebook adds to this strategy of alliance with the fetishism of commodities, however, is that the very instrument of research is a fetish. In English we have a phrase, “set a thief to catch a thief,” the idea being that a thief knows best the mind of another thief.

– Michael Taussig, Fieldwork Notebooks, 2011: 6

Eight months ago, right in the middle of my field(net)work in Mainland China, I created an archival Tumblr for my current PhD project and I started experimenting with the integration of image blogging into ethnographic research. The simple three-column, pink-background image gallery was designed as the second iteration of a similar blog I put together years before around the idea of collecting digital folklore from the Chinese Internet. That first version was simply called Chinternet, and remained online for a few months: Tumblr eventually suspended the account on charges of disseminating ‘child pornography’. I had came across a humorous picture of a naked Chinese toddler playing with a kitchen knife on Sina Weibo, and following the rather naïve assumption that whatever could be posted on a Chinese social media platform (usually the benchmark of censorship and suppression) would also be ok on Tumblr (a platform which incidentally hosts quite a lot of porn and gore content), I posted it on Chinternet without much hesitation. After a few days, in an ironic first-hand experience of cultural norms and platform governance, I found my entire Tumblr account under non-negotiable lockdown without any forewarning or take-down notice, and I was back to square one. Luckily I had all the content archived on my hard drive.

The first image I posted on the Chinternet Tumblr (now dǎ jiàngyóu), an animated .GIF of a piece of ASCII art on glittering starry background collected from an early Chinese web page.

The new incarnation of this Tumblr, which I started off by simply reposting the content of Chinternet in the original order (minus questionable pictures of minors), and which I keep updating on an almost daily basis with new items from the chronological archive of images collected during my fieldwork, is called 打酱油 dǎ jiàng yóu. In Chinese, the compound dǎ jiàngyóu literally means ‘getting soy sauce’, but in the local online slang it has been adopted as a figurative way of saying ‘minding one’s business’. I like the term for two reasons: first, it is a good example of a vernacular expression emerging from the feedback loops between mass media (the original TV news broadcast in which a recalcitrant interviewee used the locution to express his extraneity to the event), digital media (the online platforms where the episode was commented and popularized), and everyday communication (in which the compound is extremely popular). Second, as a sardonic expression of disinterest or detachment from a larger situation or social event, I find dǎ jiàngyóu to be the perfect bit of ‘local knowledge’ to explain the main argument of my doctoral dissertation: that the digital folklore circulating on Chinese digital media platforms is a great source of insights into how Internet users in China are just ‘minding their own businesses’.

“I already can’t leave the Internet / Because going online is so cool / I already can’t leave the Internet / Because going online from my company is so fast / Going online is really wild / Going online makes people happy” (anonymous graffiti poem)

Initially set up as a database to help me visualize and search through the objects appearing in my everyday digital media feeds, reveal thematic patterns, or stimulate uncanny correspondences – a sort of small-scale cultural analytics à la Manovich, or a more qualitative version of Weiboscope – dǎ jiàngyóu has become an important resource in other ways. On the one hand, each time I shared the blog with someone participating in my research, the open nature of the platform facilitated the participation of visitors, who would occasionally contribute content from their own digital media feeds, widening the scope of my data collection. On the other, as a dynamic and flexible archive of the digital objects I’m studying, the Tumblr page has become the friendliest way to kick off an interview, elicit discussions in a focus group, and present my research project in a visually interesting way to both colleagues and participants.

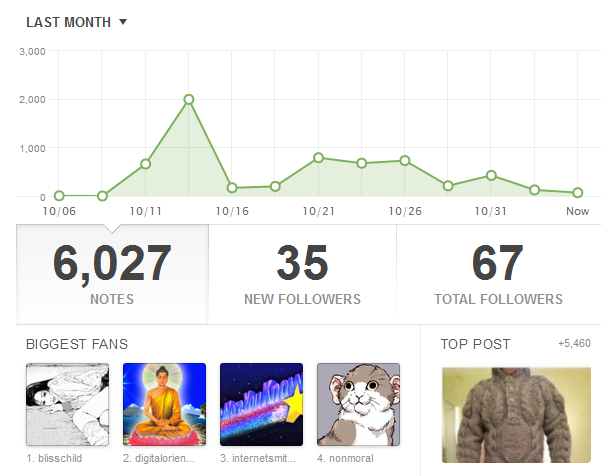

The full-body wool suit, currently the most shared and liked item on the dǎ jiàngyóu Tumblr, with more than 5,000 notes

The specific features of Tumblr as a digital media platform also contribute to the dissemination and reception of one’s work. Besides being easy to set up, open to anonymous contributions and, most importantly, still accessible in Mainland China, Tumblr also hosts a very peculiar userbase: the dynamics resulting from the quick cascading chains of liking and reposting individual entries across aesthetic communities can sometimes grant an unexpected, very large exposure to an individual post and, as a consequence, to the entire blog. As a case in point, the image above, a screen-cap of a NewSMTH BBS user showing off a full-body suit knit by his mom, successively widely shared on Sina Weibo, got more than 5,000 likes or reshares in the couple of days after I posted it on dǎ jiàngyóu, resulting in twenty-some new followers.

Tumblr analytics of one month of activity on dǎ jiàngyóu, including the peaks of content popularity and the biggest fans

As a community of users passionately engaged in consuming, contributing, curating and circulating visual content, maintaining a research output on Tumblr can also function as a test-bed for theoretical constructs and aesthetic intuitions. Through chains of serendipitous reblogs, thematic tagging and casual browsing, users tend to follow each other according to aesthetic preferences, and form overlapping communities of interest crowdsourcing different configurations of similar bodies of content, stimulating cross-pollinations, and making one feel less alone in his archival routines. Among the people who intersected dǎ jiàngyóu in these few months of activity, I happened to find some who are also approaching Chinese digital folklore from different and complementary points of view: Michelle Proksell’s netizenet, an online gallery of Chinese net art, and her visual explorations of Digital Orientalism; the vernacular styles of Accidental Chinese Hipsters, and their cooler counterparts on The Beijing Hipster; the jarring juxtapositions of textiles on Fuck Yeah Chinese Fashion, and the series of homoerotic content collected by Fuck Yeah Chinese BL. To each their own fetish!

Linguistic violence | 语言暴力

I was reading through 《平台魅力与舞台诱惑》 (Platform Glamour and Stage Lure: The Actors in China’s Internet Communication, edited by Yang Boxu and Xu Hong, 2011) when I came across this curious formulation, synthesizing the two most feared phenomena that BBS and social media seem to inevitably give rise to: the extremization of political positions, and verbal violence (政治极化与语言暴力).

你妹啊!(…your sister!)

Given historical precedents, there’s nothing unexpected in Chinese academics cautioning against the politicization of public opinion, yet the recurring demonization of “irrationality” and its symptom – “verbal violence” – still strikes me, especially when it’s seemingly unaware of, or perhaps consciously unwilling to take account of, the media specificities of online interaction, by now well explored by the relevant literature. Moreover, this leads to a constant reiteration of the idea in public discourse, with the corresponding ironic responses (locally) and sensationalist press (abroad).

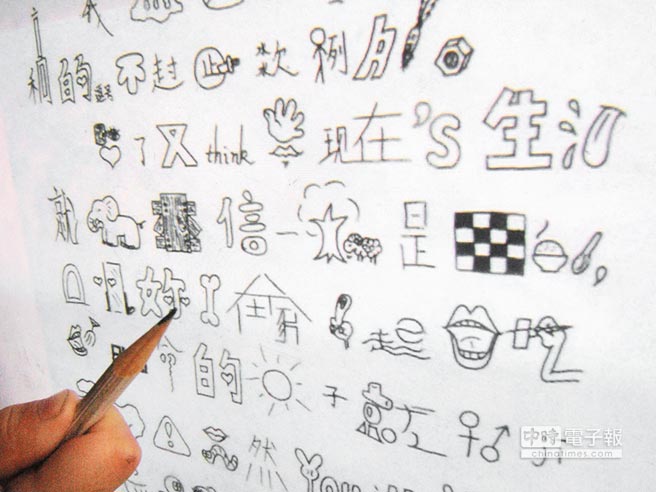

China Times’ illustration of 火星文 (Mars Script), a sort of Chinese leetspeak, which actually looks nothing like the picture

A couple of weeks ago, Taiwanese online newspaper Want Daily (旺報) reported about a Dahe.cn post authored by self-proclaimed “Internet celebrity” Du Hongchao (网路红人杜洪超, subsequently upgraded by English language press into a “Chinese academic”) complaining about the pervasiveness of sexually-charged online vernacular terms. In his words:

“From SB to Grass Mud Horse, from kubi to bige, from diaosi to diaozhatian, who has invented and disseminated this kind of Internet language? Let’s not use this coarse (cubi) vocabulary, ok?”

「从SB到草泥马,从苦逼到逼格,从屌丝到屌炸天,是谁发明和传播这种网路语言?咱能不使用这些粗鄙词汇,好吗?」

In Du Hongchao’s opinion, although some people might believe this to be an irrelevant matter, “language has the potential to infiltrate, and this kind of crisis should not be ignored” (语言有浸润作用,不该忽视这种危机). In support of his statements, Dahe.cn confirmed that their moderators have to filter and delete a large number of thread titles containing coarse wordage – like, again, Grass Mud Horse – on a daily basis.

On a closer inspection, this “incident” involving an authority-figure spewing quite trite arguments against, basically, the proliferation of f-words in online interaction, seems to be as hyped by the media as irrelevant it is deemed by Chinese digital media users. Although I couldn’t manage to track down the original post on Dahe.cn, the few mentions of it on Sina Weibo speak volumes:

As of September 8, the original post by Du Hongchao himself had 9 likes, 57 retweets and 44 comments, not exactly the numbers anybody would expect to find around a proper controversy. Moreover, most of the top comments are predictable carnivalesque offenses and ironic accusations of irrelevance, each with a few likes:

“If you never heard of him, like this post!”

“Restrain my ass! You’re really a pain in the ass! Fuck your mom!”

“We don’t have to say ni mei? Just say hehe. HEHEHEHEHEHEHEHE”

“Idiot hello, goodbye idiot”

Few other Weibo posts mention the article and comment it with ironic emphasis on the self-proclaimed celebrity of Du Hongchao:

“I don’t know if this Du Hongchao is an Internet celebrity or not, but his mother is going to become a Internet celeb-mom real fast”

In short, infotainment media – in its original reporting from Taiwan’s Want Daily and the cascading reposts by english language China watchers – seem to have fairly overstated the size of the Du Hongchao incident, and for understandable reasons: the “Chinese-academic-wants-to-curb-vulgarity” headline is a great click-bait, and rests conveniently upon the widely popular narrative of netizens vs. government that hovers around Mainland social media reporting.

Indeed, it was Mainland media that disseminated the piece of news in the first place, probably as part of a generalized effort in regulating and civilizing online (and offline) interactions. As China Youth Daily reports:

“recently, lots of new words appear in very short spans of time, and a few of them manage to make the news headlines, like meng, zan, geili, jiediqi, tucao and so on; but there are also a few that leave people baffled, like MM, dajiangyou, beiju and so on. Students not only use them all the time, but also write them down in essays, giving great headaches to elementary language teachers”

“近来每隔一段时间就会出现1批网路新语,有些成功进入新闻标题,如:萌、赞、给力、接地气、吐槽等;但有些令人莫名其妙,如:MM、打酱 油、杯具等,学生不但常常讲,还写进作文里,令初中国文老师头痛不已。”

Chinese schoolkids using vernacular terms in essays give great headaches to teachers, the argument runs

Yet, the actual “Du Hongchao incident” remains limited to a few retweets and the predictable dismissive insults normally ensuing from any plea not to indulge in vulgarities. Is this a sign that the Internet, in China as elsewhere, is a bakhtinian carnival safeguarding its own vernacular vocabulary from the intrusions of officialdom? Is the defense of debasing insults via more debasement a coherent strategy of resistance, or the mere affirmation that vernacular terms are here to stay, and that the practice of calling somebody’s sister in cause is not the most urgent social issue to confront?

Infotainment and opinion-making definitely play a part here, along with the fragmentation of carnival in personal media feeds, issue publics, and ephemeral pieces of news. Yet the official line should not be entirely ignored, especially in times in which governmental provisions and Party guidelines emphasize the push towards an adaptation of classical Marxist media theory to the relatively self-regulating spheres of digital media. The flat-ontology model envisioned by the Dean of Tsinghua’s School of Journalism and Communication Li Xiguang, in which “propaganda activists” would ideally go back to the grassroots level of digital media users and do ideological work right on the flows of user-generated content, puts the tentative and overhyped stunts à la Du Hongchao in another light:

“Using the great ship of the new media to take to the seas, the propaganda workers of the Party can take their propaganda work among the masses to the mobile community of the me-media. Through the mass line, the Party’s policies and political line will be understood and accepted by the masses”

“党的宣传工作者通过借新媒体这艘大船出海,可以把群众的宣传工作开展到移动终端的自媒体圈内”

The highly idealistic goal of this kind of flattened media culture, already practiced by Mao and Trotsky with mixed results, would be, quite honestly put by Li Xiguang himself, to build “a news and propaganda discourse system” (新闻宣传话语体系) that would “accurately, fluently and concisely transmit socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Trotsky’s armored printing-press train is the archetypal model of a flattening media machinery

On more practical grounds, this could be seen as the ideological background of policies and regulations such as the recent anti-vulgarity drive on WeChat promoted by the SIIO, “now clearly the lead Internet regulatory body in China” according to Bill Bishop. Although never explicitly linked to vernacular terms, the breadth of causes of concerns for the State Internet Information Office seems wide enough to fit whatever needed:

“Cyberspace cannot become a space full of disorder and hostility,” Jiang [Jun] said. “No country in the world allows dissemination of information of rumors, violence, cheating, sex and terrorism.”

Besides the obvious observation that actually most countries in the world do allow the dissemination of information, rumors, violence, cheating, and sex, it is clear how the SIIO claims represent the practical attempts at establishing an infrastructure of regulation to act upon when further flattening of the media system is needed.

It is not difficult to expand and reshuffle the bakhtinian carnival-officialdom dualism along the lines of Antley‘s augmented reality versus textual realism:

“Augmented reality holds that dualist conceptions obscure the workings of social interaction and power through false separation of reality into dual spheres, i.e. cyberspace and real life, when in fact there is only one reality amongst which both the digital and physical inter-operate” (2012:1038)

Antley draws on exclusively pre-digital examples of “subjects in the Russian empire protesting the intrusion of textual dualist assertions through the augmented reality discourses” such as rumors and refrains. “Constructs that allow modification, such as folktales or rumors”, argues Antley, “possess ‘high mobility’ attributes that give its content and delivery great mutability between users and/or transmitters” (1039). This “high mobility”, accelerated by the synchronous nature of much digital media dissemination, seems to be the great leveler of postdigital times, shortening the long tail of media incidents into a forgettable afterglow lost in the quick turnover of infotainment.

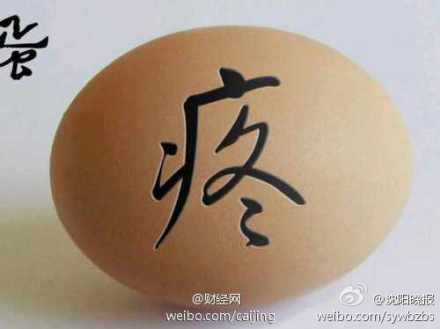

“egg-pain” (蛋疼), figuratively “a pain in the ass”

How does this relate to the cubi language decried by Du Hongchao and thrown back at him by many of his readers? Chinese academics explain that “the abuse of extreme or offensive wordage is a phenomenon of the mob of the Internet”, and that “the definition of coarse vocabulary is purposely broad to include not just crude words but other insult, words of malicious attack and extreme sarcasm”. For this reason, they continue, “we should also make our efforts to regulate and guide people in expressing their emotions in Internet, in particular to educate the young students”, for example, by “actively join discussions in online forums and adopt more rational opinion to balance and guide irrational emotions.”

Coherently with the theoretical assumptions and practical goals of a decidedly Marxist media theory, the discursive loop keeps running back and forth from not-so-veiled references to violent mobs during revolutionary times, the equation of sarcasm with abusive language, and the necessity of educating the young to rational opinions rather than irrational emotions. It’s not surprising to realize that it was precisely the popularization of a vernacular language that helped the CCP settle into power. As Rana Mitter observes:

“the arrival of an officially recognized vernacular form of written Chinese paved the way for mass literacy and the ability of the state to use education and propaganda to engage with its population (most notably under the CCP)”

Old worker lost among new four-character idioms.

References:

– Antley, J. (2012). Textual dualism and augmented reality in the Russian Empire. Future Internet, 4(4), 1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi4041037